Transfer Learning From Graph Neural Networks Trained on Quantum Chemistry

Graph neural networks trained on quantum chemical data learn a fine grained, compressed representation of molecular physics. This representation can be reused as a starting point for transfer learning, enabling accurate models on fewer than one thousand data points and addressing the challenge of generalizable learning with small datasets — link to the CJC award winning article

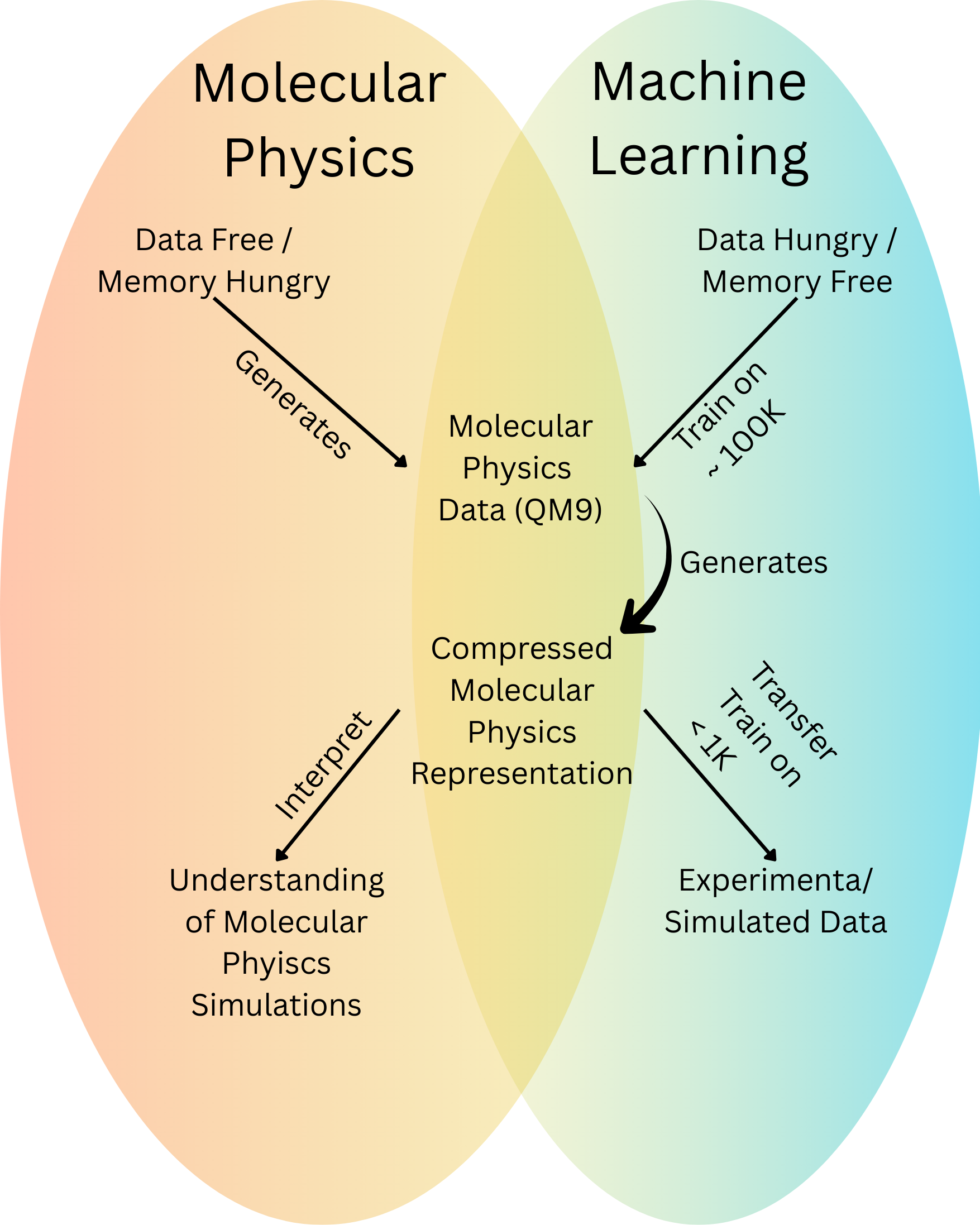

A major challenge in molecular physics is the sheer size of the problem. First principles methods treat a molecule as a network of interdependent particles, each influencing all the others. This quickly becomes memory intensive because the number of interactions scales with every added particle, and the possible electronic states grow without bound. Even modest molecules demand substantial computational resources, making these approaches difficult to scale. In short, they are memory hungry. Their advantage, however, is that they are data free they can generate high quality data for machine learning without relying on it.

Machine learning offers a complementary strength. ML models avoid the memory explosion of first principles physics, but they introduce a different bottleneck. They are data hungry. To avoid overfitting, an ML model must be trained on a very large dataset, one rich enough to span a wide variety of chemical environments, geometries, and conformations so that it can learn generalizable patterns.

The power of ML emerges when we combine these two worlds. ML models run with relatively low memory requirements, yet they can distill molecular physics into compressed, fine grained representations. When a GNN is trained on quantum chemical simulation data, it learns a compact latent space that captures much of the underlying physics. This pretrained representation provides a transparent lens into how molecular behavior organizes itself inside the model. More importantly, it serves as a powerful starting point for new learning tasks. With this representation in hand, downstream models can be trained on fewer than one thousand data points, dramatically reducing the data required for accurate prediction. In this way, transfer learning directly mitigates the data hunger of ML.

Fig 2 - Pianist learning the piano and a model of musical theory to transfer to new instruments.

Fig 1 - Physics on the left, data driven models on the right. A ML trained on physics sits in the middle (e.g., GNN), turning memory heavy calculations into a compact representation that small datasets can reuse.

Transfer Learning from Compact Representations

Transfer learning is a broader idea than its use in AI. If you have ever learned a musical instrument, you know it is impossible to progress by memorizing finger movements alone. As you practice, your mind inevitably absorbs elements of music theory chords, scales, rhythm, and harmonic structure. You are not just repeating motions; you are building an internal model of how music works. Modern AI systems behave similarly. When trained on a task grounded in a fundamental domain such as molecular physics, they do more than memorize examples. They begin to construct an internal representation of the underlying principles, which can then be reused for new tasks. This is the essence of transfer learning.

There are two main forms of transfer learning. The first is the familiar one: take a pretrained model and retrain the entire model on a new task. This is like asking a pianist to learn guitar by relearning every piano movement on the guitar. In AI terms, it means fine tuning all of the GNN’s parameters on a new property or dataset. This approach works, but it is inefficient and data hungry because GNNs contain many parameters that must be reoptimized. And musically, it makes no sense either. You do not play guitar by mimicking piano keystrokes. A guitar asks you to strum, bend notes, play riffs, and improvise. Relearning everything from scratch misses the whole point.

The second form of transfer learning is far more efficient. Instead of retraining the entire model, we extract only the learned representation—the internal features the GNN built during training. These features, the atom feature vectors (AFVs), as shown in a previous post, encode meaningful chemical principles. We then use this representation as the input to a new, lightweight model for a different property. This is similar to a musician learning a new instrument not by copying the exact motor patterns used on the piano, but by drawing on their existing understanding of musical theory. The underlying knowledge of harmony, rhythm, and structure transfers, allowing them to learn the guitar with far less time and effort. In the same way, using the AFVs allows new chemical models to be trained with dramatically fewer data and resources.

This representation level reuse dramatically reduces the amount of data needed for a new chemical task. Rather than teaching a model quantum chemistry again, we begin from a space that already encodes it. As we will show, this allows accurate models to be trained with fewer than one thousand data points, providing a practical path forward for small dataset learning in chemistry.

Regardless of which transfer learning method is used, there are two phases to transfer learning. Phase I is the pre-training phase this is the model you spend a lot of resources on, the model you have a lot of data for. In our case, this the quantum chemical simulation data. This phase generally requires lots of data points, for GNN model nearing on ~100 K datapoints. From this model a compact representation is built which can be used in the second phase. in Phase II, the model itself or a new (leaner and more appropriate model) is fine-tuned from the compact representation already built from Phase I.

Transfer Learning from GNN Pretrained on Quantum Chemical Simulations

Fig 3 - two phases to transfer learning, pre-tuning and fine-tuning

To show the phenomena of transfer learning in the fundamental domain of quantum chemistry. We carried our Phase I (pretraining) of a GNN neural network on 134 K QM9 dataset, for details on the dataset and the GNN model architecture used please visit previous post. Following this we carried out Phase II using the strategy of extracting the pretrained representation, a.k.a atom feature vectors (AFV) which also were extensively analyzed in the previous post. We then use the pre-trained representations for learning a down-stream task such as pKa, NMR, and solubility, with less than 1K datapoints.

We used very simple models for Phase II, either linear regression or a 1-layer dense neural network. The input was either the AFV representation of a single atom, or all atoms in the molecule, for size-extensive properties such as solubility. For local properties, a single AFV near the site of the local observable is enough to capture the trend.

A diagram of each of these Phase II models are shown below, one for local properties, and one for size-extensive molecular properties. Each new property or skill requires a type of architecture. For local properties like pKa and NMR