The Hidden Language of AI in Chemistry: Unifying Graph and Language Models of Chemistry

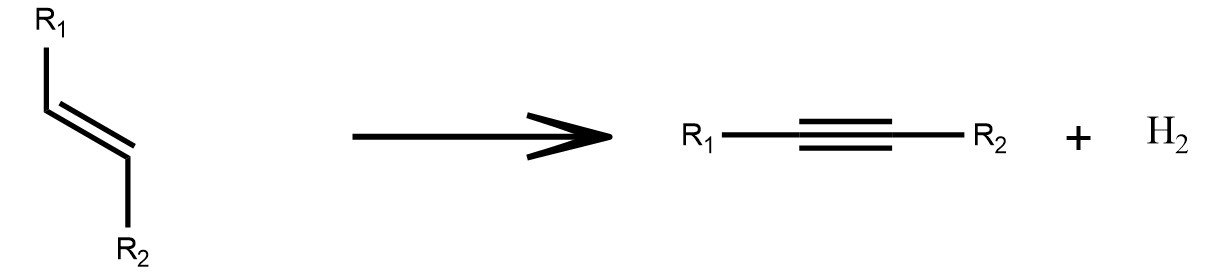

Natural language models learn meaning by organizing words into high dimensional spaces where relationships appear as directions, “King” = “Queen” - “Woman” + “Man.” Graph neural networks do the same for atoms. When trained on molecular data, they construct a latent space where reaction pathways emerge as geometric patterns, ‘reduced’ - ‘dihydrogen’ = ‘oxidized.’ — link to article

Fig 1 - t-SNE projection of the 128-D AFV space from previous post. These clusters are not randomly arranged in 128-D but arranged in reaction syntax

Average Reaction Vectors and Latent Space State Functions

If the latent space is chemically coherent for this class, the average vector should be similar for all i. That is,

In practice, this is only approximate. Real reactions vary in ways the model must reflect. Different molecules have different electronic environments, steric effects, substituent patterns, and local functional groups. These influence how the representation shifts from reactant to product. Because of this molecular diversity, the reaction vectors are similar but not identical.

In language analogy, a transformation often follows a consistent pattern without being perfectly uniform. For example, making a noun plural usually involves adding “s,” yet not every word behaves the same way. Cat becomes cats but child becomes children. The underlying idea is stable, but the transformation must adapt to the specific word. In the latent space, this shows up as similar vectors rather than one exact displacement.

Chemistry behaves the same way. Oxidizing an alcohol follows a general pattern but oxidizing an aldehyde makes a carboxylic acid which introduces oxygen along with the double bond, whereas oxidizing an alkane creates a double bond only. Different molecules respond differently depending on their electronic environment and substituents.

cat - one + many = cats

child - one + many = children

child - avg[-one + many] = childs

Well-known examples from language models shows how meaning becomes geometry. Natural language models arrange each word representations into a learned vector space such that relationships between them align along simple linear directions. For example, gender, tense, or number changes appear as consistent vector changes.

Gender Transformations

King – Man + Woman ≈ Queen

Hen– Man + Woman ≈ Chicken

He – Man + Woman ≈ She

Other Transformations

Paris – France + Italy ≈ Rome

ice – cold + hot ≈ steam

Mozart - music + physics ≈ Newton

Verb and Tense

run – running + fly ≈ flying

walk – walked + play ≈ played

write – writes + read ≈ reads

In the gender examples, ‘- Man + Woman’ is a vector transformation that takes any male-gendered word and turns it into its female counterparts. These are not hand-crafted rules, this is how the model learns to represent linguistic structure geometrically. Ordered relationships between words give rise to consistent geometric directions in a model’s latent space. Changes such as gender as stable vectors: the surrounding context stays the same, but the word shifts to a different form and meaning. This behavior is not unique to language models. It is a general consequence of learning from any structured domain. Chemistry is no exception.

Graph models of molecules operate under the same principles. In a previous post we worked out the mathematical definition of a graph neural network model. Then we tested the graph neural network with molecules from the QM9 dataset, extracted part of a trained graph neural network called the atom feature vectors (AFV) which represent a crucial part of the model’s latent space, its compressed information about each tested atom.

We saw that graph neural networks (GNNs) organize atom feature vectors into a structured latent space that reflects their functional groups. Here we extend this claim, functional group clusters are not randomly arranged in the AFV space, but in a way that respects the language of reaction formula.

Exploring the GNN latent space through reaction formulas

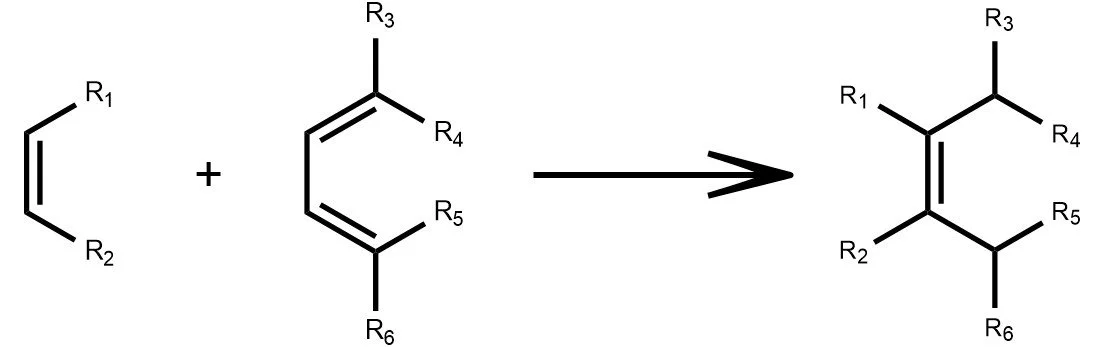

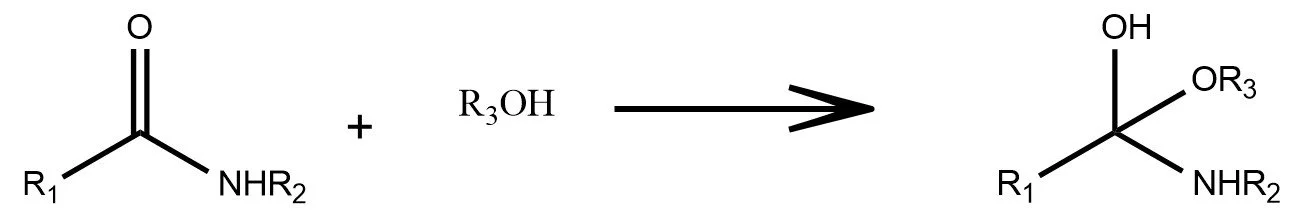

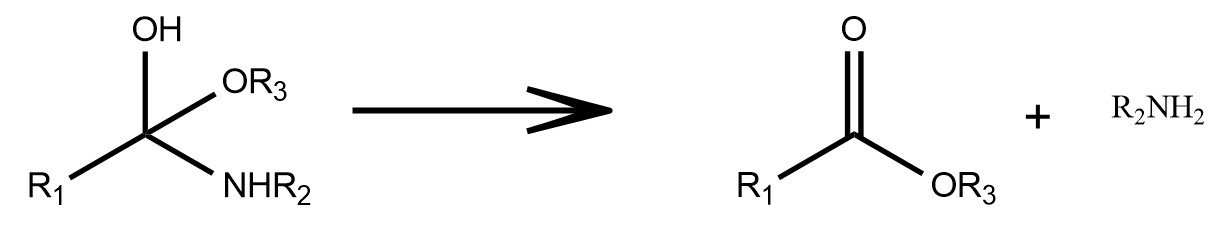

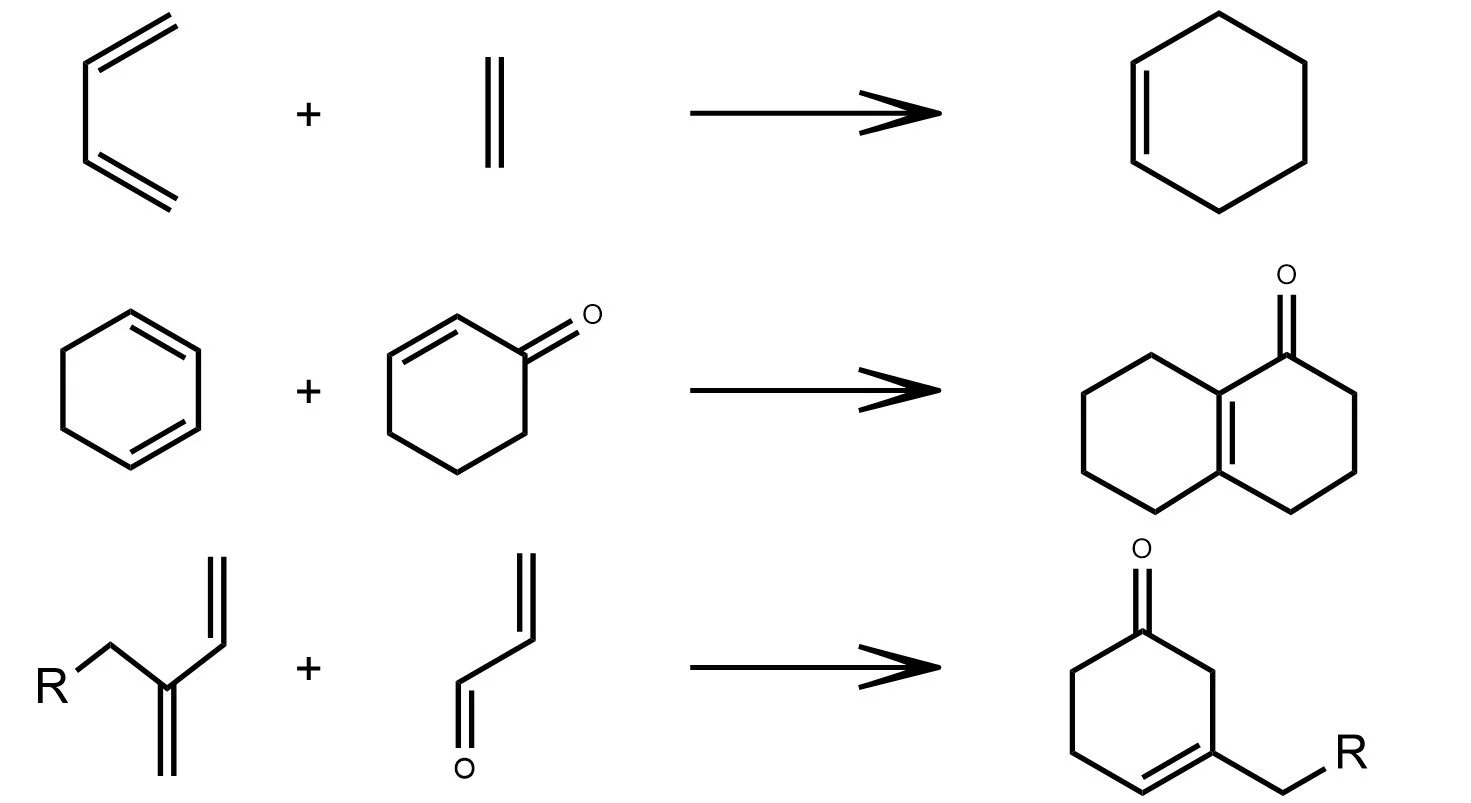

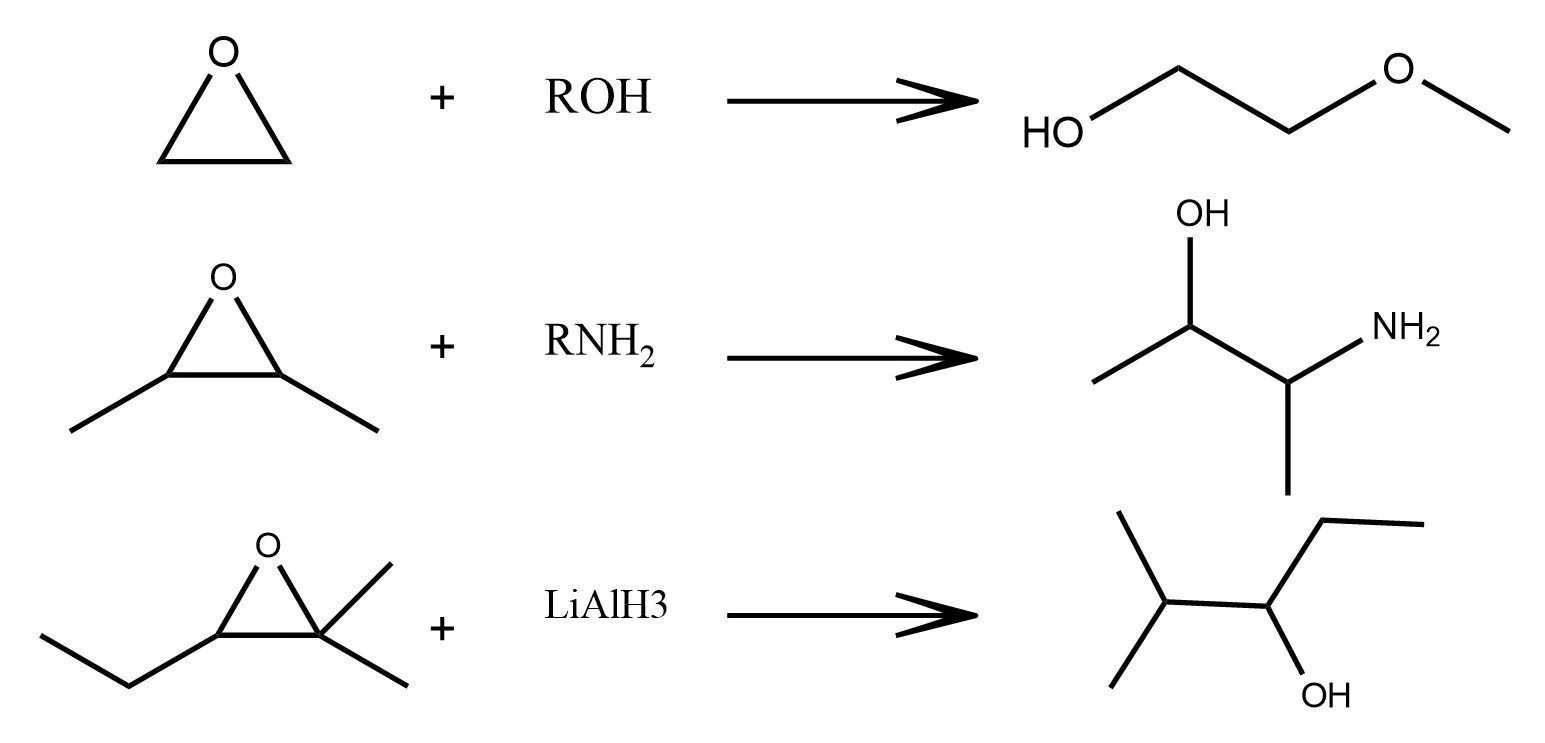

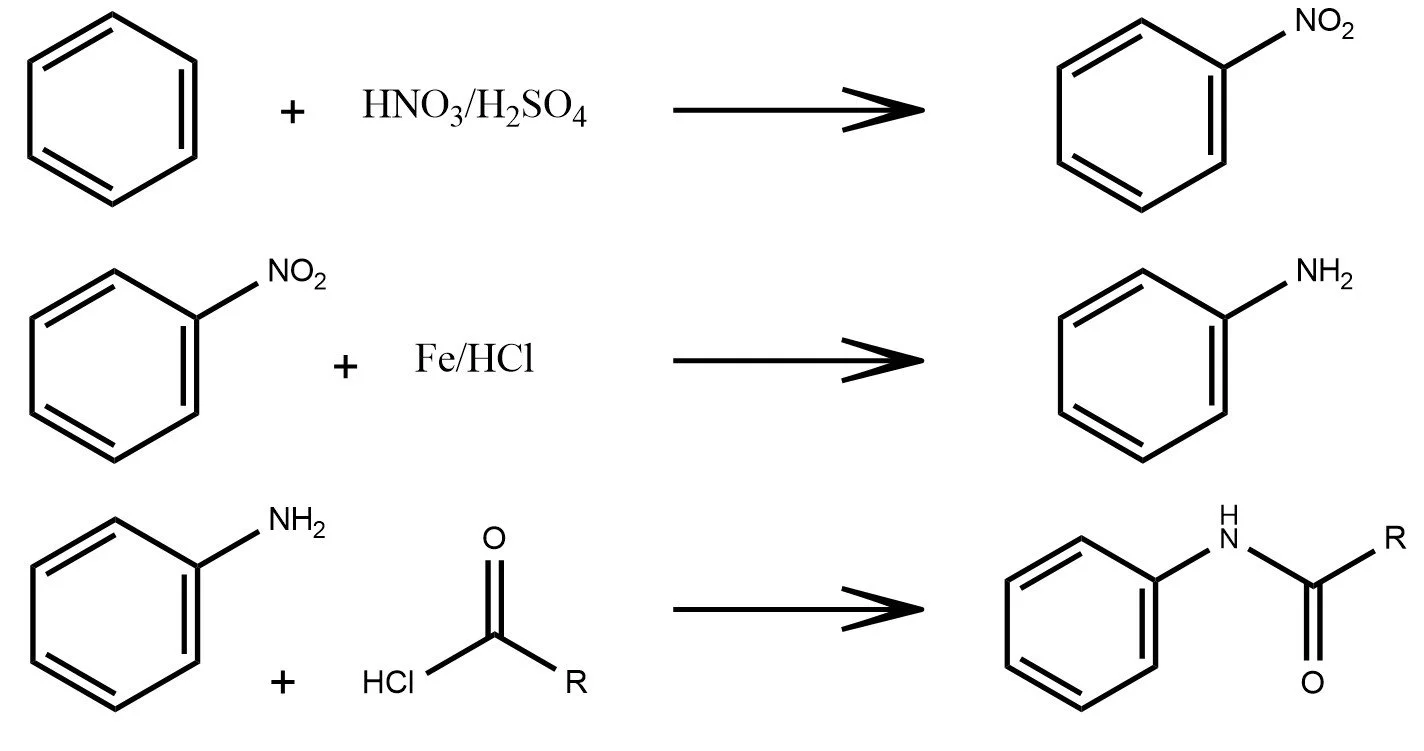

We investigate the approximate transformation that maps reactants to products by using the average product minus reactant difference vector for each reaction class—second equation above. Eleven reactions were evaluated (six shown visually), each passed through the trained GNN model. Architectural and dataset details appear in the previous post.

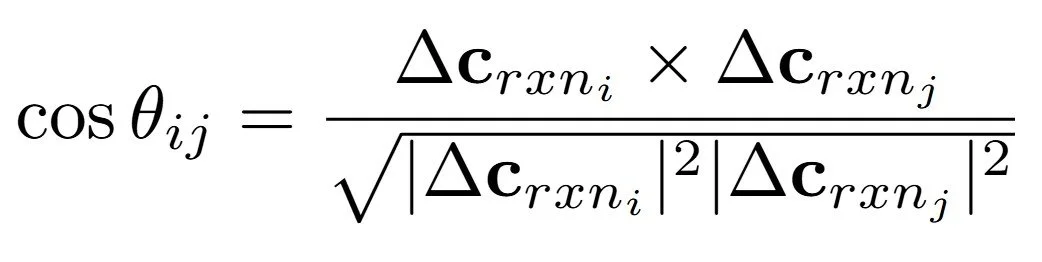

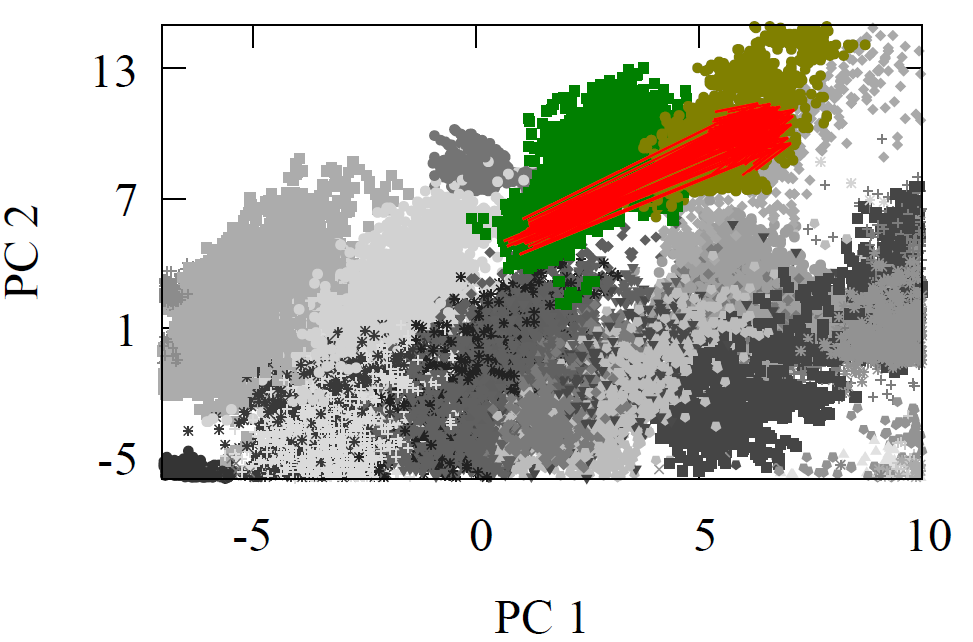

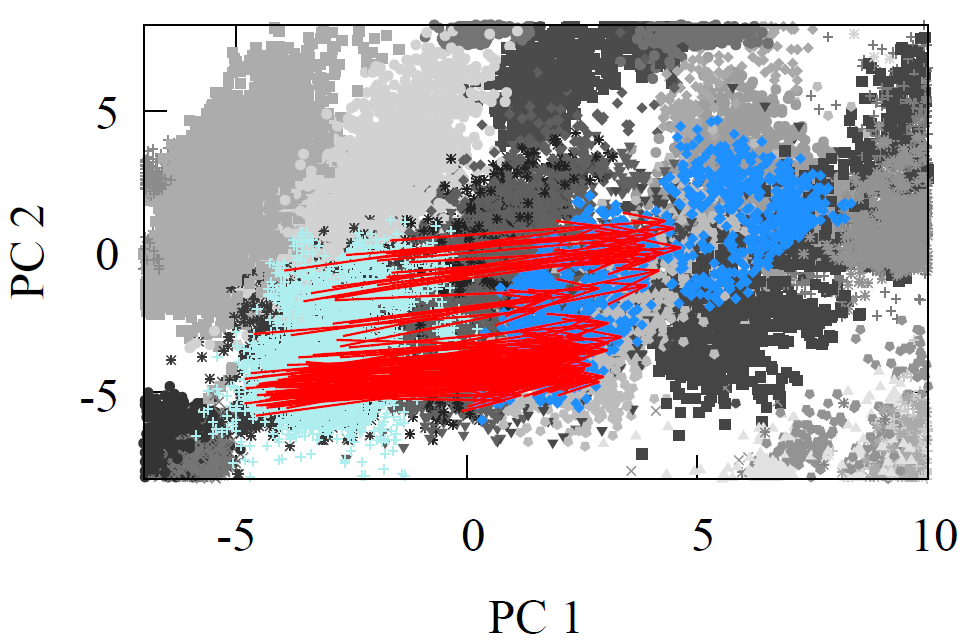

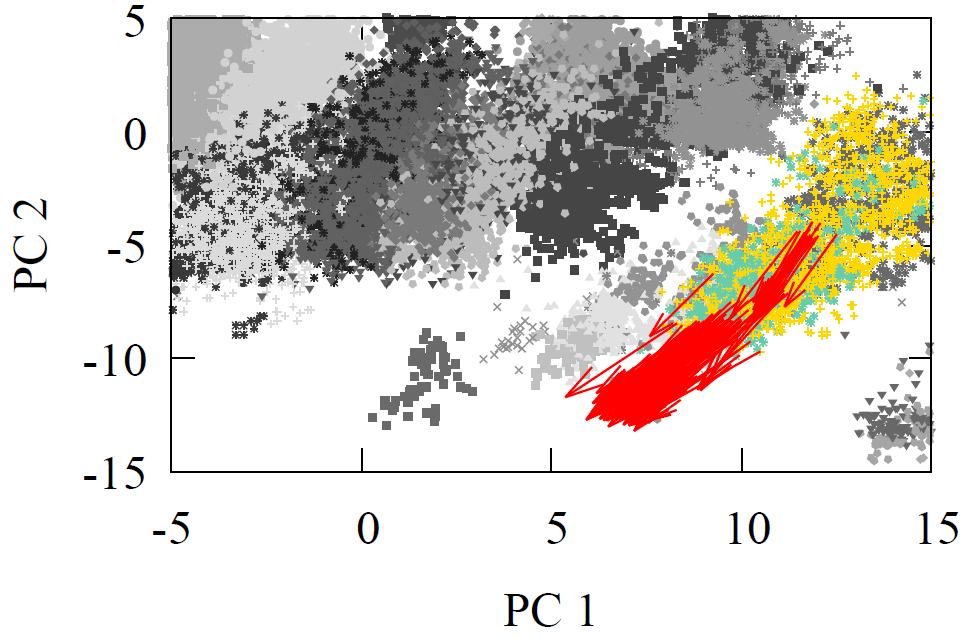

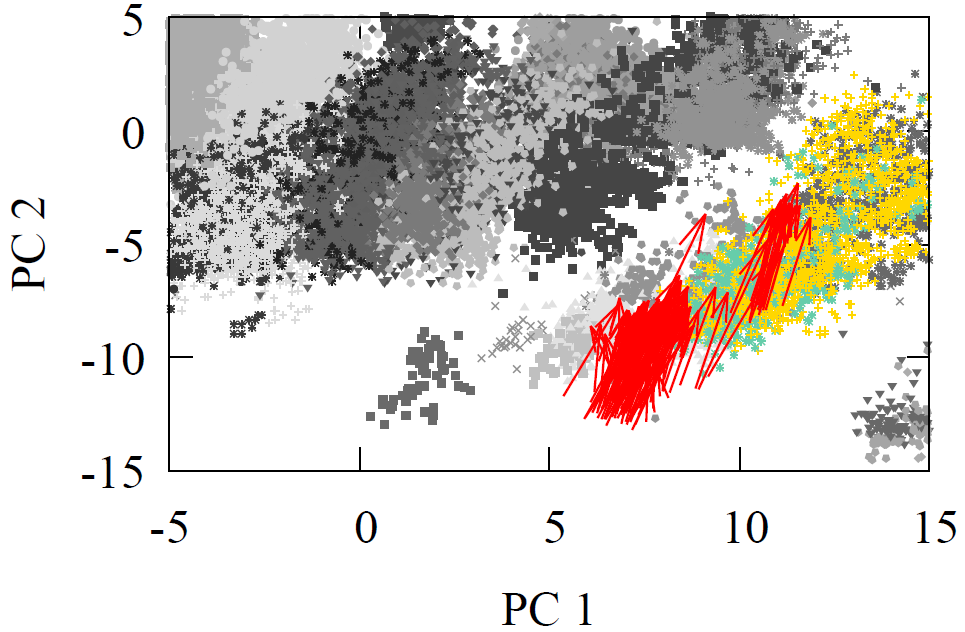

All molecules were first geometry optimized with MMFF94 or GAFF to ensure reasonable structures. As each reactant and product propagated through the network, we extracted the atom feature vector of the reaction center carbon from the final interaction layer. The product minus reactant differences were computed for every reaction. These atom feature vectors reside in a 128-D dimensional space. For visualization, we projected reactants, products, and their difference vectors into 2-D using linear PCA. The resulting projections appear below

Fig 2 - Reaction transformations explored using a 2-D PCA projection of the 128-D AFV space built by GNN trained on QM9.

It is visually clear from the first two principal components that the difference vectors are nearly parallel within each reaction class and even across related classes such as oxidations. Additionally, arrows point in the opposite direction for inverse reactions, trivially for reduction to oxidation, but non-trivially between Diels-Alder and oxidation due to the former’s removal of double around reaction center. Due to the variety of chemical reactions, two dimensional projections however cannot fully convey the underlying geometry of the latent space. Moreover, it is possible for vectors to appear aligned by chance when reduced to a plane.

To evaluate this structure in the original 128-D space, we use several metrics. Given the highly directional nature of each reaction arrow, we can use an average reaction arrow (e.g., second equation above) and then measure how often the approximate average transformtion map a reactant AFV to a product AFV whose nearest neighbor is the true product AFV generated by a full GNN pass. In other words, can we replace the full GNN pass with a average proxy. The table below summarizes these results. The GNN percentage column indicates how often the proxy transformation lands nearest to the full GNN-pass product, providing evidence of the highly-structured AFV space in terms of reaction syntax. Almost more than 2/3s of the time the proxy transformation is enough to land us near the full GNN pass on.

Table 1 - The table summarizes how many product molecules already exist in the QM9 dataset, how many new molecules are introduced by applying the reactions optimized under a given force-field, and the total size of each reaction class. The “density” column gives a simple measure of how sparse each class is in chemical space, computed as 1/total. The %GNN, %MF, and %MF/r report the results of the neighbor test a proxy evaluation of how well each proxy transformation captures the product representation relative to the true GNN or MF representation

We also compare these results with Morgan fingerprints, an alternative global molecular representation. In fingerprint space the nearest neighbor is often the reactant itself because the fingerprint encodes overall molecular similarity rather than local changes at the reaction center. After removing the reactant from the neighbor set, a similar directional pattern appears although it is weaker and less coherent than the pattern in GNN embedding space. This difference reflects the atom centered nature of GNN representations which capture the chemistry of reaction centers more effectively than global descriptors such as Morgan fingerprints.

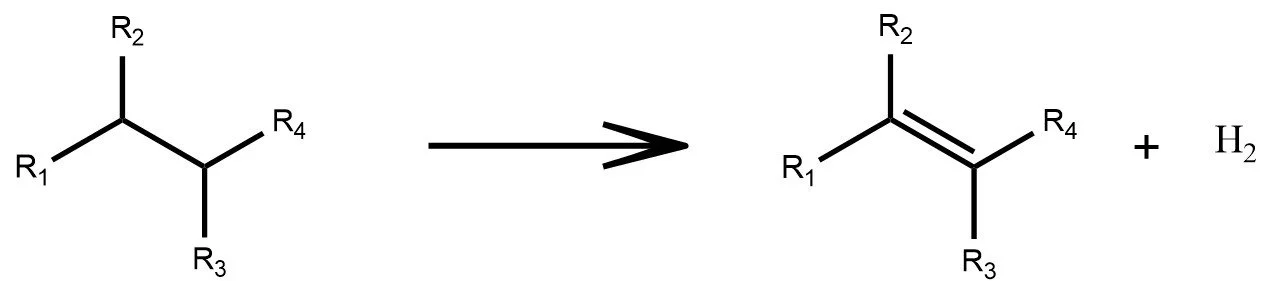

Additionally, we use the cosine similarity between different average transformation vectors to find that they encode syntactical relationship between the reaction formulas. A cosine similarity between two vectors is given as

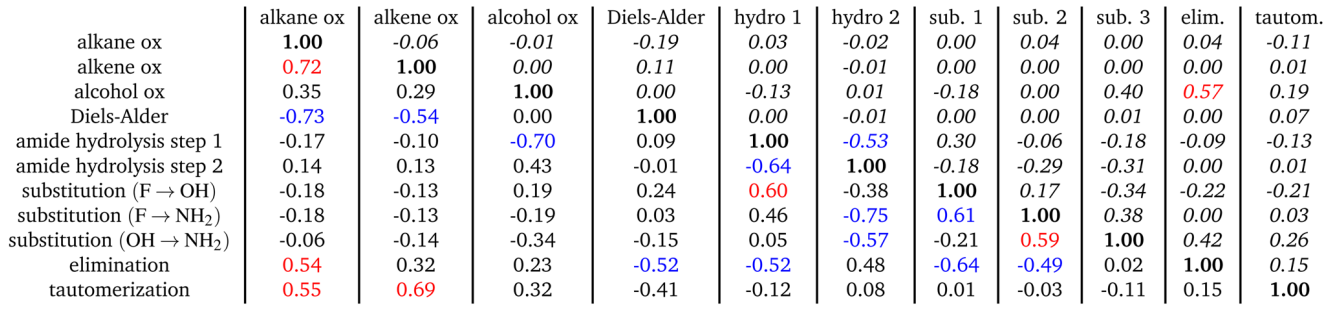

The table below shows the result of computing cosine similarities between our eleven tested reactions. The lower left triangle reports similarities between average reaction vectors in the GNN atom feature vector space. The upper right triangle reports similarities between vectors built from Morgan fingerprints, a classical feature engineering approach where each molecule is mapped to a binary vector that encodes circular atom neighborhoods. Morgan fingerprints capture which structural fragments are present, but they do not naturally define a smooth geometry of change.

Table 2 - Cosine similarity between the various average reaction vectors for GNN embedding vectors(lower triangle) and for Morgan Fingerprints (upper triangle, italic). Cosine similarities above0.50 are depicted in red and below −0.50 in blue.

In the GNN space we see stronger and more coherent geometric structure (lower triangle of matrix). Reaction classes that are chemically related, such as oxidations, elimination, and tautomerization, show high similarity and cluster together. Reverse transformations appear with strong negative alignment, for example between oxidation and its corresponding reduction reactions, and between Diels Alder formation and the oxidation that removes the double bond at the same center. Other interesting arrangements include the reverse alignment of nucleophilic addition of step amide hydrolysis with the nucleophilic leaving mechanism. Or the reverse alignment between elimination and cycloaddition or nucleophilic addition. Other entries fall closer to zero, reflecting reaction classes that create products unrelated in syntax and therefore occupy their own directions.

The Morgan fingerprint similarities (upper triangle of matrix) are weaker and noisier. Because this representation is global and molecule centered, it tends to emphasize overall structural overlap rather than the local change at the reaction center. Some broad patterns still appear once the reactant itself is removed from the neighbor set, but the relationships are less sharp than in the GNN space. This contrast highlights that atom centered GNN embeddings are better suited to capturing the syntax of reaction formulas, while traditional fingerprints behave more like coarse global descriptors.

Conclusions

Together, these results show that a graph neural network trained only on molecules, and never on reactions, still learns a latent space where chemical reactivity appears in a structured and interpretable form. Reaction classes map to consistent displacement vectors, chemically related transformations cluster, reverse reactions invert cleanly, and unrelated classes fall into orthogonal directions. This organization is far more coherent than what we observe with traditional Morgan fingerprints, whose discrete and non geometric nature cannot express transformation structure.

The geometry uncovered here suggests that the model is capturing something closer to the “syntax” of chemical change rather than merely memorizing molecular fragments. The state function analogy helps frame this behavior: what matters in the representation is the shift from reactant to product, not the mechanistic path connecting them. This gives us a compact way to describe reactions as movements through latent space.

While approximate, this structure opens a door to richer reaction aware applications. Reaction vectors may help guide product prediction, support generative design along chemically meaningful directions, or serve as building blocks for synthesis planning frameworks grounded in continuous representations. These possibilities make clear that the latent spaces learned by GNNs contain far more actionable chemical knowledge than their training objectives alone would suggest.

Singular to Plural

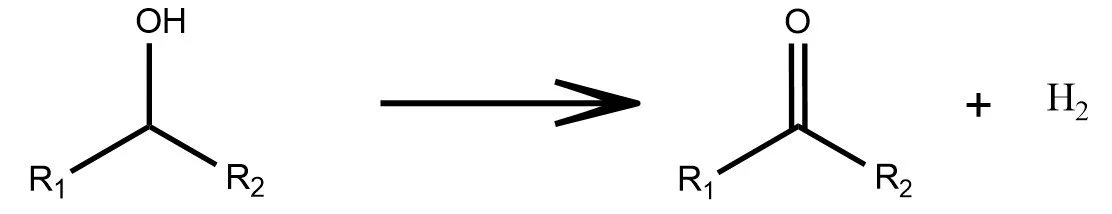

Reduced to Oxidized

References

For those interested in diving deeper into the details, all connecting citations and results discussed in this post can be found in our full article: A. M. El-Samman and S. De Baerdemacker, “amide - amine + alcohol = carboxylic acid. Chemical reactions as linear algebraic analogies in graph neural networks,” ChemRxiv. 2024; doi:10.26434/chemrxiv-2024-fmck4. This reference provides a comprehensive exploration of how chemical reactions are modeled as linear algebraic analogies within the GNN decision-making framework. Be sure to check it out for the full breakdown!

Redox

Diels-Alder

Epoxide Ring-Opening

Multi-Step Transformations

As shown in the examples above, a reaction formula is analogous to a sentence in natural language. Reactants and reagents act as the “words,” the reaction arrow plays the role of the “verb,” and the products form the resulting “object.” Just as a sentence transforms meaning while preserving its structure, a chemical equation transforms matter under consistent chemical rules.

In the latent space of a trained graph neural network, this analogy appears again. Although the model is trained only on individual molecules and never on reactions, the embeddings of reactants and products still align to form clear, consistent reaction directions. These shifts resemble the way state functions depend only on initial and final states, not on the mechanistic path. The latent space has quietly organized chemistry so that many reaction types oxidation, hydrolysis, cycloadditions, and multi step sequences map to well defined geometric movements. In this sense, the model begins to “speak chemistry.”

To explore this structure, we extract latent vectors for reactants and products and analyze their differences, much like comparing state variables. This perspective offers a foundation for future tasks such as synthesis planning, reaction prediction, and generative molecular design, all supported by a chemically coherent representation.

If the organization of the latent space is reminiscent of state functions, meaning that regardless of the reaction pathway the final result is determined only by the initial and final states, then we can treat reactions in the latent space the same way. The mechanistic path does not appear in the representation. What matters is how the model positions the reactant and how it positions the product.

This lets us describe a reaction as a simple displacement in latent space. For a given reaction class for example alcohol oxidation we embed each reactant and product and extract their latent vectors, and take their average: